Op-ed for World Refugee Day

By Katrina Jorene Maliamauv, Executive Director, Amnesty International Malaysia

19 June 2021

A mother has died.

A mother has died, and her death is a footnote in a story of broken engines, borders and body counts. On 8th June 2020, a boat that was adrift in open, treacherous seas landed off the coast of Langkawi. On board, were almost three hundred Rohingya refugees. The news reported that the authorities found one body among the barely living in need of refuge. The authorities lamented that the engine was broken, and as such, they could not send them back into the seas. The refugees were given water, and then they were detained. Ten days later, another news article – two security sources revealed that once the engine had been fixed, the authorities were making plans to send the refugees back into the sea.

On the 19th of June 2021, Prof Dato’ Noor Aziah, SUHAKAM’s commissioner for children, revealed during a panel that the woman who died on that boat was the mother of two young children. These two children, and the over two hundred others who survived ethnic cleansing in Myanmar and the arduous journey at sea, have been detained for over a year in Kem Bina Negara Wawasan, Langkawi. Is this the vision we want to build our country on?

A mother has died and there are no flowers for her grave, no grieving rituals. A mother died while her children were pressed up against other bodies, on a packed boat awash with stinging sea water and human waste, in the wide-open seas. A mother died and her children survived, only to be detained for months and months without an end in sight. From the mouths of sharks, to the jaws of hell.

Sixty kilometres from Langkawi, in the border-village of Wang Kelian, in the smallest state in Malaysia, the stories of the mass graves wait to be told. At least 130 bodies, believed to be refugees and migrants, were found in shallow, unmarked graves in 2015. A Royal Commission of Inquiry was set up to investigate, and news stories trickled out – allegations of cover-ups by the police were revealed, of the authorities knowing that humans were held in cages and did little to stop it, of camps and evidence being destroyed. The full report was completed but never made public.

People die, and their stories are not told.

In Bukit Mertajam, a few hours away from Langkawi and Wang Kelian, refugees were pulled out of their homes and made to sit on the ground. We are at the height of the pandemic, Malaysians are told to stay home for the sake of communal protection, yet refugees are grouped on the ground, questioned by uniformed men. The Home Minister stands mightily flanked by enforcement officers and journalists. We are told that Malaysians in the community are frustrated by the lack of jobs, the dirty neighbourhood, the drugs. The Home Minister assures Malaysians that the government will protect their rights. The cameras pan over the refugees, their faces and bodies. A child squirms in their mother’s lap.

These stories are snapshots of the thousands of ways we, as a country, choose not only to abandon people in the hour of their greatest need, but how we actively hunt them down, let them drown, subject infants and the elderly to systematic forms of discrimination and violence. These are stories of the overwhelming trauma that refugees endure, not just from the persecution they are fleeing, but from the ongoing trauma of living in a society that actively denies them their basic human rights.

The stories of the boats are about people seeking safety and survival, and our desire to let them drown instead. We use words like “detain” as if these are processes that exist separate from the human person. Detention is harmful, detention is traumatising. Over and over again it has been documented (and made known to the authorities) how even short periods of detention lead to depression, suicidal ideations, self-harm; how it fundamentally affects the development of a child; how the harms stay with you even years after release. Yet we make the choice to do this repeatedly to tens of thousands of people. We build more places of detention, we cut off lifelines for refugees by denying UNHCR access.

In 2019, the government allocated RM139 million to operate detention centres. By contrast, in the 2021 budget, a mere RM20 million was allocated for ‘women development’ while RM397 million was set up for social welfare. Who benefits from investing millions more into traumatising thousands of people? Why do we invest in structures of violence, instead of protection of rights? How are Malaysians protected when harm is inflicted?

The story of Wang Kelian is about how people will seek paths to safety and survival especially when there are no official routes to safety. It’s about enforcement officials who know of mass graves and humans kept in cages, but choose to destroy evidence and cover up the truth. The story of Wang Kelian is about the astounding lack of avenues for justice and accountability. It’s about how despite the Royal Commission of Inquiry report being completed, the findings are not revealed; it’s about how the state denies us our right to information.

In the discovery of Wang Kelian, we are reminded that the person committing harms here isn’t the refugee who is trying to find a path to safety from ethnic cleansing and persecution but it’s all who are involved in corruption and in the systematic dehumanisation of migrants and refugees. The victims of Wang Kelian and their loved ones suffer in the gravest ways, but they’re not the only ones. When we enable dehumanisation, we disconnect ourselves from our humanity.

We all lose when the human rights of any person are diminished; we are all harmed when violence is normalised; we are all threatened when the State feels like it can tear into the bodies of people over inadequate paperwork (the Immigration Act allows for whipping; the kind of judicial caning practised here meet the definitions of torture under international law). We all suffer when we play into the hands of the powerful who say only some of us can survive, only some of our lives are worth saving. This is true for refugees who are pushed back into the sea, it is true for the clamouring for vaccines in the middle of a pandemic.

When the death of migrants in detention centres or refugee slave camps and mass graves in Wang Kelian are not met with truth, healing, reparations and justice, we cannot be surprised when Ganapathy or Sivabalan or the hundreds more deaths in custody are not met with open, transparent public inquiries, accountability and justice. When migrant Rayhan Kabir is hunted down, detained and deported for speaking the truth that is plain to all – that migrants are suffering in the pandemic – then we cannot be stunned when artist Fahmi Reza is repeatedly arrested, questioned, dragged to court for reflecting back our reality in his art. We all lose when the degradation of human rights is normalised.

It is likely that the people interviewed by the Home Minister in Bukit Mertajam, lamenting about their Rohingya neighbours, are facing difficult lives. So many people are suffering right now. Perhaps they’re trying to make sense of the lack of jobs, their dirty neighbourhoods, the overcrowded homes, the fact that people in their community are turning to drugs as a way to cope. In the absence of an analysis for why the systems are failing them, perhaps it’s not surprising that they’ve latched on to racist, xenophobic narratives.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful though if one of the most powerful Ministers in Malaysia, upon hearing about these grievances chose instead to address the needs and rights of all in the community, instead of pitting one group of people (refugees, migrant) against another (Malaysian)? Wouldn’t we all be better off if instead of inflicting more trauma by denying refugees their rights, our government chose to repair harms instead? What if our elected officials used their immense powers and resources to meet housing needs for all in that neighbourhood – Malaysians, refugees, stateless people, migrants? What if the authorities made sure no employer or corporation could exploit workers or pay pitiful wages, and what if investments were made to make sure there are dignified, decent jobs with living wages for all? What if the authorities made the choice to work with the community to address the sources of harm and trauma that are driving people to use drugs as a way to cope? What if we set up mental health support networks for people living in that neighbourhood – for refugees, for survivors of ethnic cleansing, , for children who were abused, for people suffering PTSD, for the numerous harms many of us have had to endure?

We deserve a government that governs – that looks at problems and doesn’t look for a group of people to scapegoat and blame, but works to find solutions for all. “State obligation” to protect, uphold, defend and fulfil the human rights of all people (not just citizens) within their geographical boundaries is a key tenet in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, of which Malaysia has committed to. What if we held our government to this? What if we chose defending the dignity and rights of migrants, refugees, stateless people, the poor, ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, indigenous peoples, LGBT persons instead of playing into the false belief that only some of us should have rights and protection? What if we created lasting infrastructures of care for all of us, Malaysian, migrant, refugee, stateless – wouldn’t we all win? If we can invest millions into systems that create spirals of harm, why not into systems that affirm dignity and fulfil human rights for all? Don’t we, as people in this country, deserve that?

Don’t surrender to the myth that we cannot have a better world; that we cannot make other choices; that there aren’t enough resources to share; that these crises are too big to address or that we don’t know what to do. At the start of the pandemic, when we were scared and confused and in lockdown, so many of us found ways to care and support and love and nourish each other, people we knew and strangers. #KitaJagaKita and other mutual aid initiatives showed us how in times of great need, when we interrupted the “normal ways” of being, we could find ways to care. The systems are set up to normalise violence, to disconnect us from our humanity – don’t let it.

Refugees in their very existence show us the incredible resilience, ingenuity, strength, possibility of the human spirit; that refugee children, elderly, teenagers not only survive displacement, torture, ethnic cleansing but can make it to a foreign land thousands of miles away and set up schools, raise families, be leaders, create art, and feed communities, then surely we can imagine and create better worlds, other ways of being. People seeking asylum deserve to be met with a system and culture of care, refuge, and a fulfilment of their rights. Malaysians deserve that too.

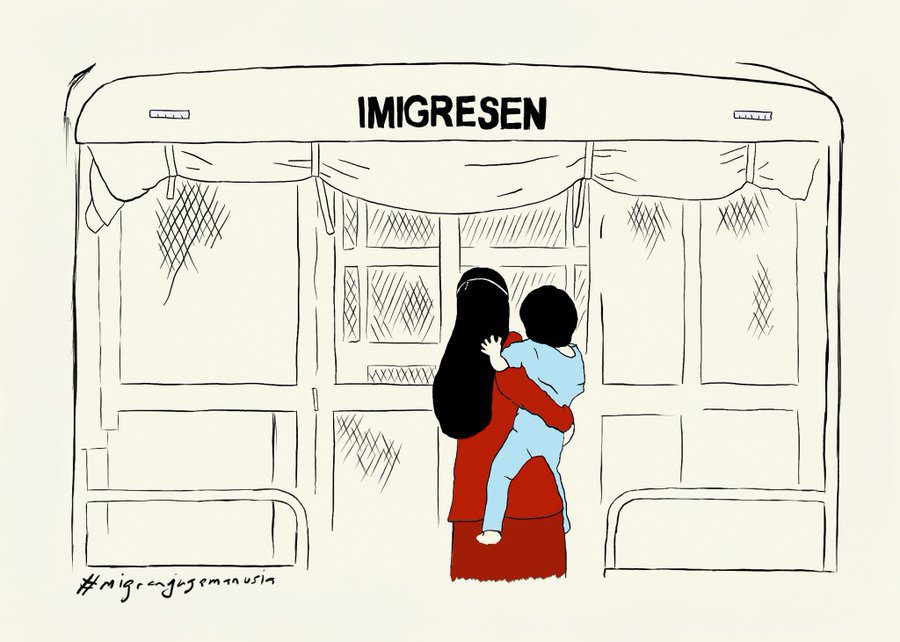

#MigranJugaManusia

*Graphic credit to Ezrena Marwan. Follow graphic designer @ezrenamarwan on Twitter.