We know that, together, we can end the death penalty everywhere.

Every day, people are executed and sentenced to death by the state as punishment for a variety of crimes – sometimes for acts that should not be criminalized. In some countries, it can be for drug-related offences, in others it is reserved for terrorism-related acts and murder.

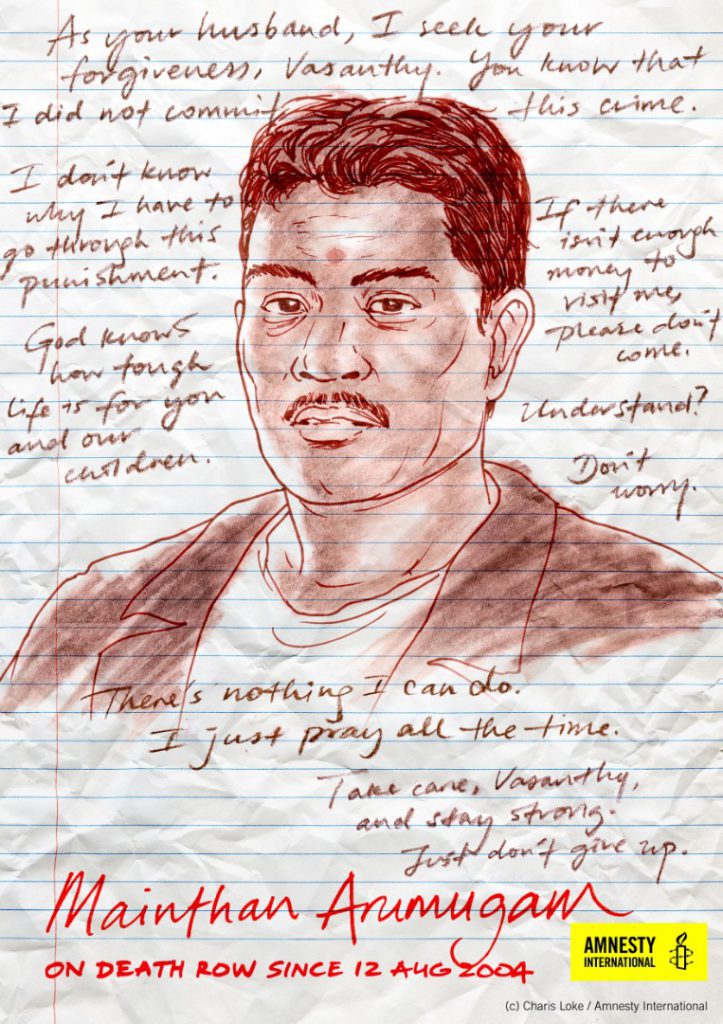

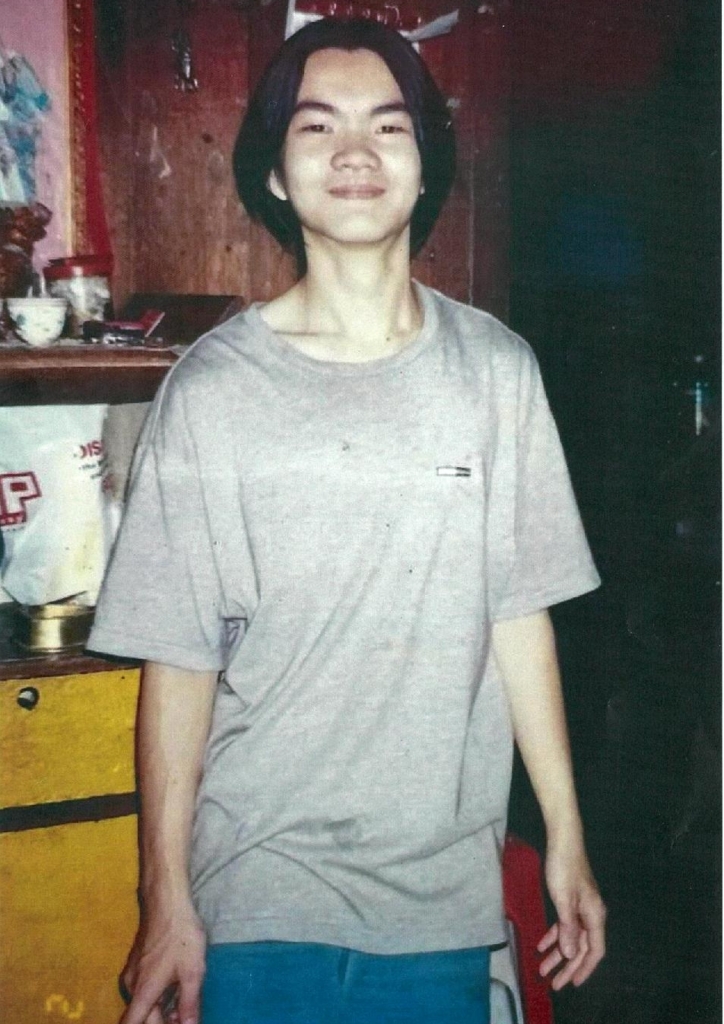

Some countries execute people who were under the age of 18 when the crime for which they have been convicted was committed, others use the death penalty against people with mental and intellectual disabilities and several others apply the death penalty after unfair trials – in clear violation of international law and standards. People can spend years on death row, not knowing when their time is up, or whether they will see their families one last time.

The death penalty is the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment. Amnesty International opposes the death penalty in all cases without exception – regardless of who is accused, the nature or circumstances of the crime, guilt or innocence or method of execution.

KEY FACTS AND FIGURES

BASED ON STATISTICS OBTAINED IN 2019

All death penalty will be abolished. Full stop.

Liew Vui Keong, de facto Law Minister, 10 October 2018

Current Status of the Death Penalty in Malaysia

(as of 10 October 2023)

The death penalty is currently retained for 27 offences in Malaysia, and in recent years has been used mostly for murder and drug trafficking. As of September 2023, 906 people were reported to be on death row in Malaysia, more than 45% of which represent foreign nationals. Of the total, more than half have been convicted of drug trafficking. Some ethnic minorities are over-represented on death row, while the limited available information indicates that a large proportion of those on death row are people with less advantaged socio-economic backgrounds.

In the past few years, however, there have been important reforms that have brought Malaysia closer towards full abolition of the death penalty. In July 2018, the government imposed a nation-wide moratorium on executions. Although the courts in Malaysia continued sentencing people to death, there have been no executions known to have taken place since the moratorium came into force.

In 2023, Malaysia took the critical step of abolishing the mandatory death penalty and introducing sentencing discretion for all offenses for which it was applicable. Also included in this set of reforms was the repeal of natural life imprisonment as well as the abolition of the death penalty in full for seven offences. This leaves Malaysia with 27 offenses that are still punishable by death subject to the discretion of the courts.

Since 12 September 2023, a resentencing process has been underway granting those already under the sentence of death and natural life imprisonment in Malaysia an opportunity to have their sentences reviewed and possibly commuted. Amnesty International Malaysia urges authorities to ensure that the resentencing process is made to be a fair and meaningful opportunity for all those involved, and that Malaysia continues working towards ending this cruel, inhumane, and degrading punishment once and for all.

ACT 847

Revision of Sentence of Death and Imprisonment for Natural Life

(Temporary Jurisdiction of The Federal Court) Bill 2023

CLICK HERE TO VIEW A STEP-BY-STEP FLOWCHART

(ISSUED BY THE MALAYSIAN GOVERNMENT ON 12 SEPTEMBER 2023)

DETAILING THE RESENTENCING PROCESS